(from Herrera)

(from Herrera) (from Herrera)

(from Herrera)

CONTENTS

The Sacred Hymns of Pachacutec (a selection)

The hymns of Pachacutec Inca Yupanqui, composed for the Situa ceremony around 1440-1450, are among the world's great sacred poetry.

The eleven hymns, or jaillis, in Quechua verse, were sung to the accompaniment of instruments during the annual Inca ceremony of the Situa Raymi, held at the first new moon after the Spring equinox.

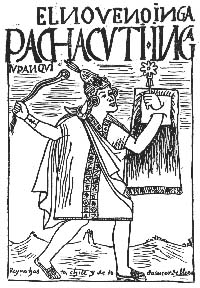

Pachacutec, considered by many to be the greatest Inca emperor, transformed Manco Capac's vision into Tawantinsuyu, Land of the Four Directions, the Inca empire. One can compare Manco Capac - legendary Inca demiurge, mythical founder and bringer of civilization - with King Arthur, Prometheus or Quetzalcóatl; one can compare Pachacutec - historical leader of an expanding new socio-political world order, a new Weltanschauung - with Charlemagne, Alexander the Great, Napoleon or Mao Tse Tung (another extraordinary poet).

In appreciation of the sacred Inca hymns, the great Quechua scholar Jesus Lara writes, "Among the hymns... there are fragments of profound beauty, interpreters of a high level of spirituality reached by the Inca people. Many of them seduce by their transparent simplicity, for the elemental gratitude in them for the deity who creates and governs, who grants sustenance, peace and happiness. Many captivate by their elevation contiguous with metaphysic. All by the emotional force that palpitates in them."

The Sacred Hymns1.

Oh Creator, root of all,

Wiracocha, end of all,

Lord in shining garments

who infuses life and sets all things in order,

saying, "Let there be man! Let there be woman!"

Molder, maker,

to all things you have given life:

watch over them,

keep them living prosperously, fortunately

in safety and peace.

Where are you?

Outside? Inside?

Above this world in the clouds?

Below this world in the shades?

Hear me!

Answer me!

Take my words to your heart!

For ages without end

let me live,

grasp me in your arms,

hold me in your hands,

receive this offering

wherever you are, my Lord,

my Wiracocha.

1.

A teqse Wiraqocha

qaylla Wiraqocha

tukapu aknupu Wiracochan

kamaq, churaq

"Qhari kachun, warmi kachun,"

nispa.

Ilut'aq, ruraq

kamasqayki,

churasqayki

qasilla qespilla kawsamusaq

Maypin kanki?

Hawapichu?

Ukhupichu?

Phuyupichu?

Llanthupichu?

Uyariway!

Hay niway!

Iniway!

Imay pachakama,

hayk'ay pachakama

kawsachiway

marq'ariway

hat'alliway

kay qusqaytari chaskiway

maypis kaspapis

Wirayuchaya.

2: Prayer that the people may multiply

CreatorLord of the Lake,

Wiracocha provider,

industrious Wiracocha

in shining clothes:

Let man live well,

let woman live well,

let the peoples multiply,

live blessed and prosperous lives.

Preserve what you have infused with life

for ages without end,

hold it in your hand.

2: Oración para que multipliquen las gentes

Wiracochan

Apuqochan

T'itu Wiraqochan

wallpay wana Wiraqochan

tukapu aknupu Wiraqochan

runa yachakichun,

sarmi yachakuchun

mirachun llaqta pacha

qasilla qespilla kachun

kamasqaykita waqaychay

hat'alliy

imay pachakama,

hayk'ay pachakama.

3: To all the spirits of placesCreator, end of all things

root of all

Lord of the Lake

active diligent Wiracocha,

Lord of Mountains

Lord of Prayers

Lord of Rituals

Lord without measure,

Creator, end of all,

who rewards and grants:

Let the communities and peoples prosper

and also those who journey outside or within.

3: A todas las huacas

Qaylla Wiraqochan

teqse Wiraqochan

Apuqochan

wallpay wana Wiraqochan

chanka Wiraqochan

aksa Wiraqochan

hatun Wirayochan

qaylla Wiraqochanta

qankuna aynichiq hunichiq

llaqta runa yachakuq qhapaq

hawaypi ukhuypi purispapas.

4.O Lord

fortunate, happy, victorious Wiracocha,

merciful and compassionate toward the people:

Before you stand your servants and the poor

to whom you have given life and put in their places:

Let them be happy and blessed

with their children and descendants;

let them not fall into veiled dangers

along the lonely road;

let them live many years

without weakening or loss,

let them eat, let them drink.

4.

O Wiraqochan

kusi usapuq hayllipu

Wiraqochaya

runa khuya maywa

kaymi runa yana waqchiyki

runayki kamasqayki,

churasqayki

qasi qespilla kakuchun

warmaywan churinwan

ch'in nanta

ama watequintawan

yuyachunchu

unay wata kawsachun

mana allqaspa,

manana p'itispa

mikhukuchun, uqyakuchun

5.O, my Lord,

my Creator, origin of all,

diligent worker

who infuses life and order into all,

saying, "Let them eat,

let them drink in this world:"

Increase the potatoes and corn,

all the foods

of those to whom you have given life,

whom you have established.

You who orders,

who fulfills what you have decreed,

let them increase.

So the people do not suffer and,

not suffering, believe in you.

Let it not frost

let it not hail,

preserve all things in peace.

5.

O Wiraqochaya

teqse Wiraqochaya

wallparillaq

kamaq, churaq

"Kay hurin pachapi

mikhuchun uqyachun,"

nispa.

Churasqaykiqta,

kamasqaykiqta

mikhuynin yachachun papa sara

imaymaná mikhunqan kachun

nisqaykita kamachiq mirachiq

mana muchunanpaq

mana muchuspa qanta ininanpaq

ama qasachunchu,

ama chikchichunchu

qasilla waqaychamuy.

6: Prayer to the SunLord Wiracocha,

Who says

"Let there be day, let there be night!"

Who says,

"Let there be dawn, let it grow light!"

Who makes the Sun, your son,

move happy and blessed each day,

so that man whom you have made has light:

My Wiracocha,

shine on your Inca people,

illuminate your servants,

whom you have shepherded,

let them live

happy and blessed

preserve them

in peace,

free of sickness, free of pain.

6: Oración al Sol

Wiraqocha

"P'unchaw kachun, tuta kachun,"

nispa niq.

"Paqarichun, illarichun,"

nispa niq.

P'unchaw churikiqta

qasillaqta qespillaqta purichiq

runa ruwasqaykipta

k'anchay k'anchay kananpaq

Wiraqochaya

qasilla qespilla punchaw Inka

Runa yana michisqaykiqta

killariy k'anchariy

ama unquchispa, ama nanachispa

qasiqta qespiqta waqaychaspa.

Traditions of poetry and song were deeply engraved in Inca culture, encompassing both sacred and secular forms, shared by the common people and the aristocracy. Prayer songs, ceremonial songs, work songs and love songs were part of the texture of daily life. Poetry, music and dance were integral to all the great Inca religious festivals. Each region throughout the empire retained its language and culture, and cultivated its own fine arts, as well as taking on the superimposed Quechua and Inca culture. On special occasions theatrical dramas were performed with interludes of poetry and music. Only one complete ancient Inca drama has come down to us, the great "Apu Ollantay," in which Pachacutec is a major character.

Jaillis - sacred hymns - were prayers and philosophical ponderings. Inca Priests greeted each sunrise and sunset singing jaillis, usually accompanied by music, beseeching Tijsi Wiracocha (The Creator), Inti (the Sun), Illapa (Thunder-Lightning), Pachamama (The Earth Mother), Mamaquilla (the Moon), and all the huacas (spirits of places) to grant health, prosperity and happiness for the people, the Inca and the empire. Sacred hymns were usually composed by poets who were also priests.

The sacred jailli was considered the highest poetic form, but there were other jaillis as well. Jaillis encompassed historical and agricultural modes and themes. Heroic hymns celebrated the military exploits of the Inca kings and warriors. Unfortunately no heroic jaillis have survived, but we have a number of anonymous agricultural hymns. These jaillis were sung by the working people during sowing and harvesting, particularly during collective work in the fields of the Sun and of the Inca, the fields that not only supported the religious establishment and the governing aristocracy, but also formed the common stores which were distributed to the people in years of poor harvests.

Quechua poets liked their verses brief and without obvious artifice. Arawikujs didn't care about metrics, and scorned technical rigidity. The meters of their verses were determined by the inner necessities of meaning and poetics. Inside the forms of the songs there was great flexibility. The rhythm was the natural fluidity of the language. The number of syllables in each line was highly mutable. A line of poetry usually consisted of only five or six syllables, and rarely more than eight. Rhyme and assonance were common but not necessary. Many Quechua words have the same endings. Blank verses were common.

Quechua (Qhëshwa) - or, more properly, Runasimi, meaning literally "People Mouth" - is an agglutinative language, adding syllables onto a root to form long meaningful words. By the addition of small particles to Quechua verbs, one can express numerous subtleties of thought and emotion. Many words have several synonyms, each with a slight twist of meaning. Runasimi contains many onomatopoetic words. Although outlawed for a period by the Spaniards after the revolt of Tupac Amaru II, Quechua survived and has about ten million speakers today. It is described by native speakers as an extraordinarily expressive idiom.

(from

Huamán Poma)

(from

Huamán Poma)

Pachacutec's hymns have come down to us in a manuscript entitled "Fables and Rites of the Incas" ("Fábulas y Ritos de los Incas"), written between 1570 and 1584 by Cristóbal de Molina, priest of the hospital for native people in Cuzco. Some believe that Molina was a mestizo.

Although he seemed to have known Quechua fluently, there are many lines in the jaillis that are confusing or unintelligible to native Quechua speakers and scholars today. The language we have them in can be read in a variety of ways. However the manuscript we have is not the original, but a copy, probably made by someone who did not know Quechua and who easily might have copied many words incorrectly.

I am using a comparison of the original Molina with the Rozas, Lara, Rowe and Urbano reconstructions as the basis for these translations, referring also to the other reconstructions and Spanish translations. I am assuming that the small variations between the repeated hymns are copyist's errors.

There are biographies of Pachacutec by J. Imbelloni (1946) and M. R. T. de Diaz Canseco (1953).

Copyright © 2005 by John Curl. All Rights Reserved.

|

|

|

|

|

|